A unique experimental typewriter stored in a New York state basement for decades turned out to be a one-of-a-kind piece of communications history. According to an announcement from Stanford University, historians and one unsuspecting granddaughter have rediscovered the long-missing MingKwai machine.

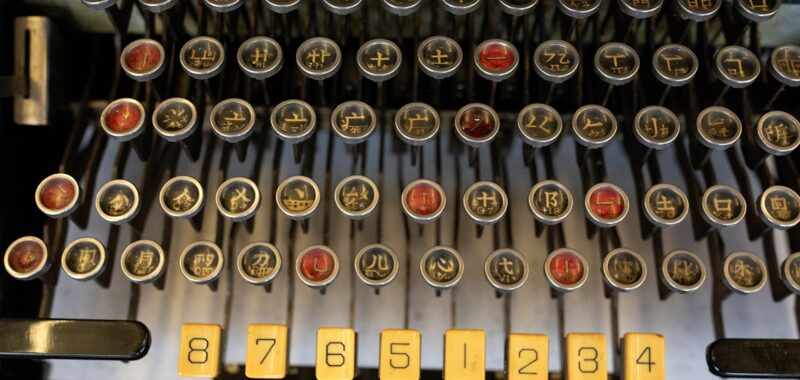

Earlier this year, Jennifer Felix and her husband were working to clean out her recently deceased grandfather’s home when they came across a large, extremely heavy typewriting device. However, instead of a more traditional setup the contraption featured five rows of keys topped with Chinese characters. After reaching out for help online, Felix realized her grandfather had been the owner of the MingKwai—one man’s innovative, if ultimately doomed, attempt to incorporate the Chinese language onto a mechanical typewriter.

A challenging typewriter

English has it easy. The 26 standard character phonetic alphabet is pretty simple to memorize, especially when compared to symbolic written languages like Mandarin Chinese. While official lists range anywhere from 80,000–10,000 symbols, even an everyday Mandarin dictionary can contain as many as 20,000 unique icons. Today’s modern computer keyboards frequently rely on the Cangje input method developed by Chu Bong-Foo in 1976 that can be overlaid on a QWERTY setup–the standard keyboard most of us know. But over three decades before that, an author, translator, and cultural commentator named Lin Yutang attempted a completely different approach for typing in his native language.

Translating to “Clear and Fast,” Lin began designing the MingKwai sometime during the 1940s. Instead of trying to overlay Cangje onto English buttons, his 72-key invention transformed sequential mechanical typing into a search-based process that foreshadowed today’s computer operations.

“The depression of keys did not result in the inscription of corresponding symbols, according to the classic what-you-type-is-what-you-get convention, but instead served as steps in the process of finding one’s desired Chinese characters from within the machine’s mechanical hard drive, and then inscribing them on the page,” Stanford scholar Thomas Mullaney wrote in his 2018 book, The Chinese Typewriter: A History.

How the MingKwai ‘worked’

Here’s how the MingKwai ostensibly worked: First, pressing a key on one of the top three rows initiated internal mechanisms to rotate towards a set of characters. Selecting a second key from one of the middle two rows then narrowed down that selection to eight characters displayed in a window Lin nicknamed the “magic eye.” Users lastly pressed the numerical corresponding to the desired character, which MingKwai then put to paper.

“Lin invented a machine that altered the very act of mechanical inscription by transforming inscription into a process of searching,” explained Mullaney. “The MingKwai Chinese typewriter combined ‘search’ and ‘writing’ for arguably the first time in history, anticipating a human-computer interaction now referred to as input, or shuru in Chinese.”

Lin commissioned the Carl E. Krum Company to build the only known MingKwai prototype in 1947. Unfortunately, the concept never managed to generate enough interest to finance its mass production. He eventually sold his MingKwai and its rights to the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, the business that employed his grandfather as a machinist. At some point in the years afterwards, the MingKwai wound up in the possession of Jennifer Felix’s grandfather, where it remained until just recently.

Asking the experts… and crowdsourcing

While Felix was unsure about the machine’s purpose at first, it didn’t take long before she realized what was in her hands—or, given its weight, on her table. Her husband’s initial post to social media garnered hundreds of responses from experts, museum curators, and scholars, many pointing to the long-lost MingKwai and Mullaney’s book.

After reaching out to Mullaney, Felix was confident in what they had in their possession. To ensure the piece’s preservation, she eventually offered the MingKwai to Stanford. In its new home, Lin’s remarkable experiment will soon be available for research, academic analysis, and public exhibits.