It happens maybe once in a writer’s life, if it happens at all: A narrative path is established, and then without warning, it swerves in a new direction that feels like a gift. This is how Lili Anolik found herself digging through the mildewed trash pile of Eve Babitz’s personal effects after her death in late 2021. The author and contributing editor to Vanity Fair was searching for material to add to a new edition of her Babitz biography, “Hollywood’s Eve,” but wound up sniffing out an entirely new project.

Babitz’s sister, Mirandi, had summoned Anolik to Eve’s apartment, informing her that, tucked deep into a hall closet, there existed a number of sealed boxes. “I opened one,” Mirandi told Anolik via a FaceTime call. “You’re not going to believe what’s in it. Letters. Lots of letters.”

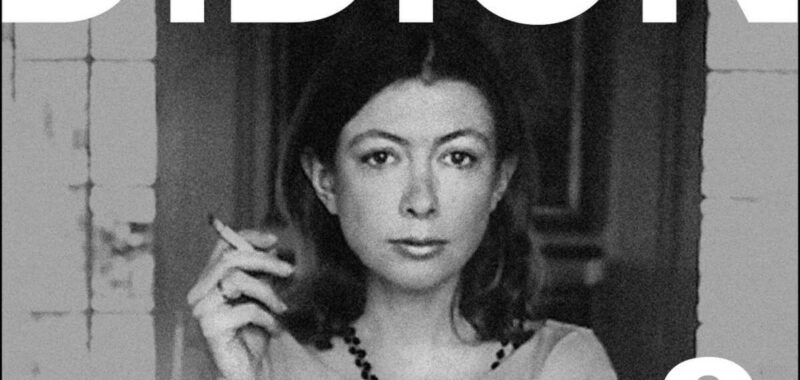

Thus began Anolik’s trip back into Babitz’s past via a large cache of correspondence that revealed, among other things, her sometimes convivial, often fraught relationship with Joan Didion when the writer, who was nine years older, was the queen bee of L.A.’s lit scene and a key figure in Babitz’s creative life.

After reading the letters, Anolik ditched her plans to revise “Hollywood’s Eve,” pivoting instead to write “Didion & Babitz,” an essential chronicle of a literary friendship. It also serves as an MRI into the inner life of Didion, who has been somewhat of a frustratingly inscrutable presence.

“Didion & Babitz” opens a new aperture. Babitz, the daughter of a classical violinist, learned about the transformative power of art and life at an early age. And she found herself in the right place at the right time: Hollywood at the dawn of the ’60s, “with its appeal to the irrational and the unreal,” writes Anolik, “its provocation of desire and volatility; its worship of sex and spectacle.” There, Babitz found the ideal milieu for her free-form libertinism, sharing pitchers of Schlitz at Barney’s Beanery with the emergent artists of the decade — Ed Ruscha, Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell — and famously posed nude while playing chess with Marcel Duchamp at a local art museum in 1963.

Earl McGrath, a cultural gadabout who had first encountered Babitz sharing a bed with the road manager for the Mamas and the Papas, brought her to Didion’s Franklin Avenue home in 1967 for one of her legendary parties. A friendship between the two women was forged; Didion, who would publish “Slouching Toward Bethlehem” the following year, had found an emissary into the darker corners of the city’s cultural life.

Where Didion was ordered, Babitz was an improviser, an artist by inclination rather than design. According to Anolik, Didion wanted to be famous while Babitz wanted to suck the marrow out of life. Didion’s work often alluded to a rebellious past, but Babitz was the true bohemian, Anolik says.

“When Joan makes certain statements about herself in her early essays, she’s not actually describing herself,” says Anolik, who considers the contrast between the two writers fascinating. “Joan was in a sorority in high school; she was a joiner. Eve was the outcast.”

“Didion & Babitz,” available Nov. 12, probes this Janus-like contrast until a sharp picture forms of Didion as the ambitious careerist and Babitz as her muse, who subsequently becomes a writer herself. Babitz’s life is the source code for her best books, 1974’s “Eve’s Hollywood” and 1977’s “Slow Days, Fast Company”; her stories are ecstatically, deliriously alive, charged with sexual energy and deadly wit. After Anolik’s 2014 Vanity Fair profile of Babitz, the writer enjoyed a revival, and her books came back in print, showcasing an original voice that consciously or not, is the antithesis of Didion’s coolly detached reportage.

Babitz’s letters reveal a complex touch-and-go friendship between the two: Didion jump-started Babitz’s literary career by writing a letter of recommendation to Rolling Stone then-editor Grover Lewis, who published Babitz’s story “The Sheik.” Another letter reveals that Didion edited “Eve’s Hollywood,” something that Babitz, in her countless conversations with Anolik for her 2019 biography, had never mentioned. Didion also helped to get Babitz’s collage art into Vogue. “Joan had benevolent impulses toward Eve,” says Anolik. “She wanted to help her.”

Yet, less than a year after Rolling Stone published “The Sheik” in 1972, Babitz fired off a pointed missive to Didion, taking her to task for her refusal to acknowledge the ways in which sexism had impeded the artistic progress of women. “Would you be allowed to write if you weren’t so physically unthreatening?” Babitz writes. “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?”

The relationship had taken a turn. “Where Eve once seemed wild and inspired to Joan,” writes Anolik, “she now seemed slack and slothful. Where Joan once seemed meticulous and masterly to Eve, she now seemed dogged and doctrinaire.”

Joan was now “Joan Didion,” much to Eve’s dismay. “Eve didn’t want to come off as professional in any way,” says Anolik. “She thought that kind of careerism was antithetical to what art was all about. She believed in the notion of pursuing art in and of itself. Eve bristled at Joan’s ambition but, of course, she absolutely wanted that kind of career.”

Babitz, by Anolik’s estimation, had one great book in her: “Slow Days, Fast Company,” a collection of stories that touch on her romantic relationships with Ruscha’s brother, Paul, and Rolling Stone’s Lewis, as well as “the politesse of threesomes, sleeping on the roof of the patio of the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel and what to wear when taking cocaine on acid,” among other things.

“Everything came together for Eve with ‘Slow Days, Fast Company,’” says Anolik. “She was just the right mix of self-confident and self-doubting. She had the right editor in Vicky Wilson. She had the right boyfriend in Paul Ruscha. And she was on just the right amount of drugs. She was using coke but not abusing coke. It was the perfect storm, so she wrote the perfect book.”

Anolik is less charitable about Babitz’s subsequent work, which she considers to be attenuated and strained, lacking the buzzy exuberance of “Slow Days, Fast Company.” Perhaps it was Babitz’s lack of self-discipline, or her excessive drug use, or the incipient onset of Huntington’s disease, which would eventually take her life.

Didion would go on to write “The White Album,” her classic 1979 collection of essays, and move to New York before publishing two memoirs — 2005’s “The Year of Magical Thinking” and 2011’s “Blue Nights” — that became mammoth bestsellers. She would end up dying a few days after Babitz in 2021.

“You can’t tell the story of Eve without Joan, and vice versa,” says Anolik. “They needed each other on some level.”